Anguilla Quilt 2021

Rachel Wallis in collaboration with Mariame Kaba

Created during a 2020-2021 Project Nia Artist Residency

7.5 ft x 5 ft

Plant dyed and linoleum block printed and digitally printed cotton, hemp and linen fabric, embroidery and hand quilting thread, glass beads, block printing ink, cotton batting.

Photographed by Bryce Laughlin Photography

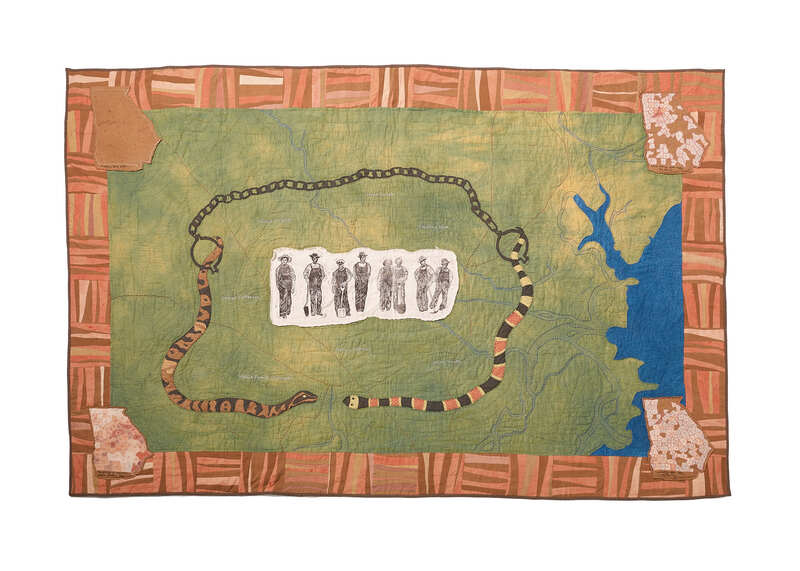

When Mariame Kaba invited me to be the first Project Nia artist in residence, and create a quilt illustrating the history of a group of prison laborers killed by their captors in Georgia in the 1940s, I was both honored and overwhelmed. Every quilt tells a story. They tell the story of births, marriages, and deaths. They tell stories with the materials they are made of; the techniques used; the love, and time, and labor invested in their creation. And they have been used by incredible artists and makers for centuries to tell powerful stories of resistance, love, family, and loss in communities around the world.

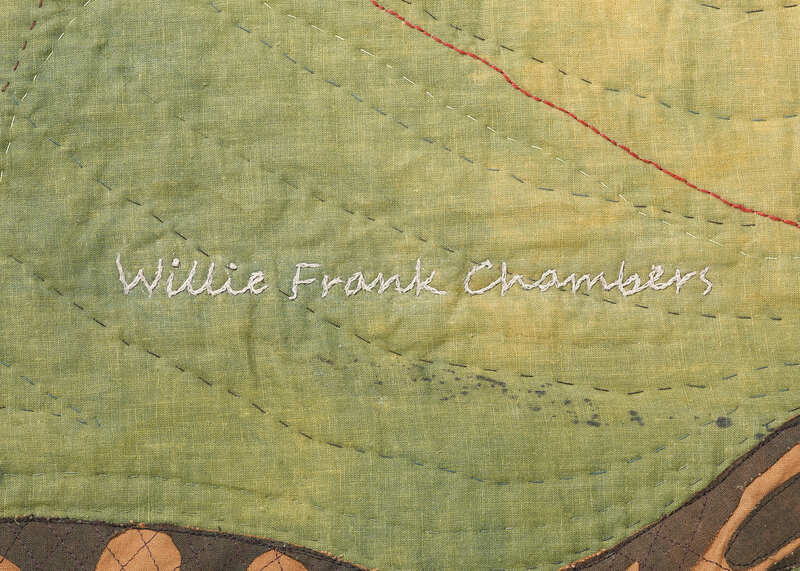

At the same time, the story of the Anguilla prison massacre is not an easy one to tell. We know so little about the victims and the circumstances surrounding their deaths. We have their names:

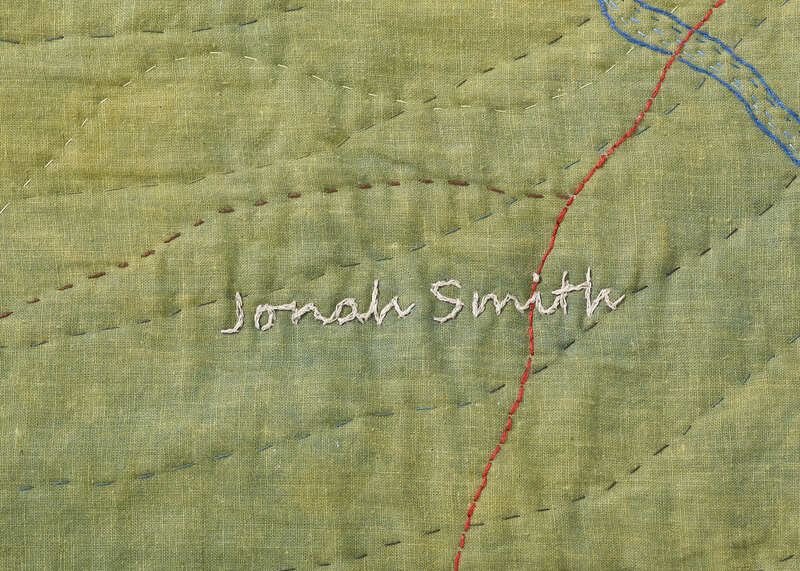

Jonah Smith

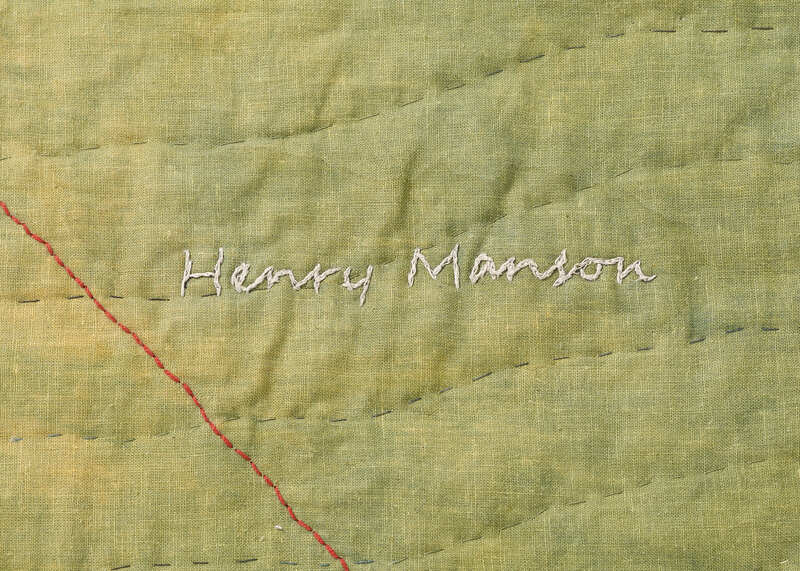

Henry Manson

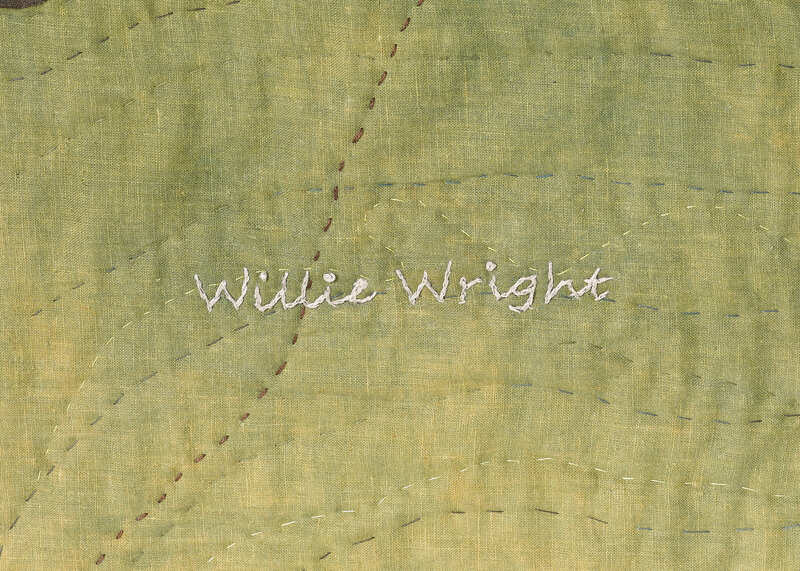

Willie Wright

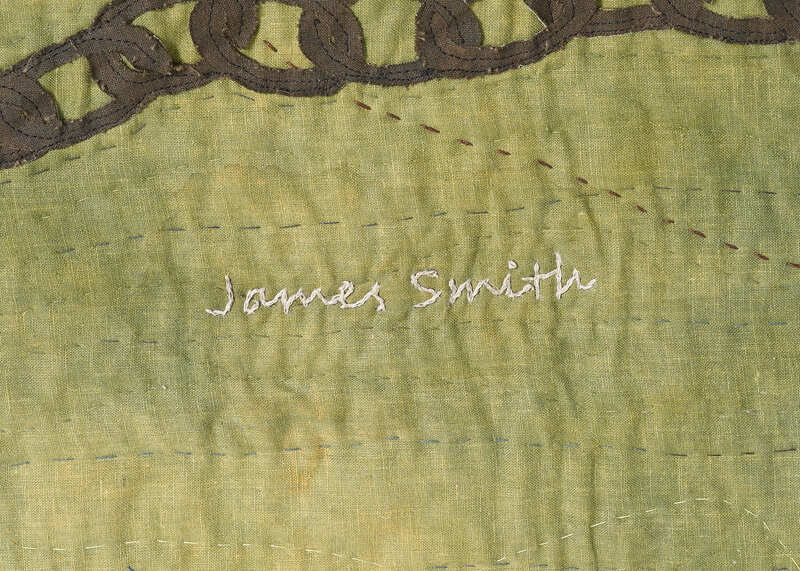

James Smith

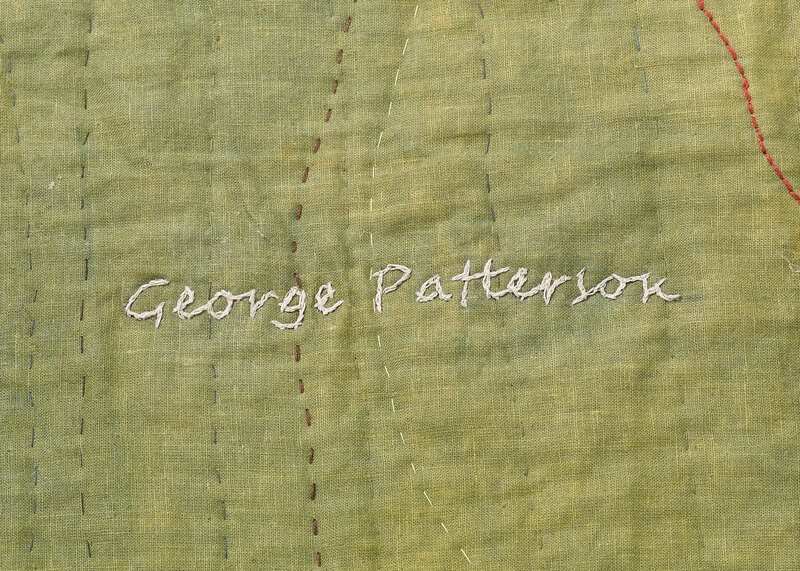

George Patterson

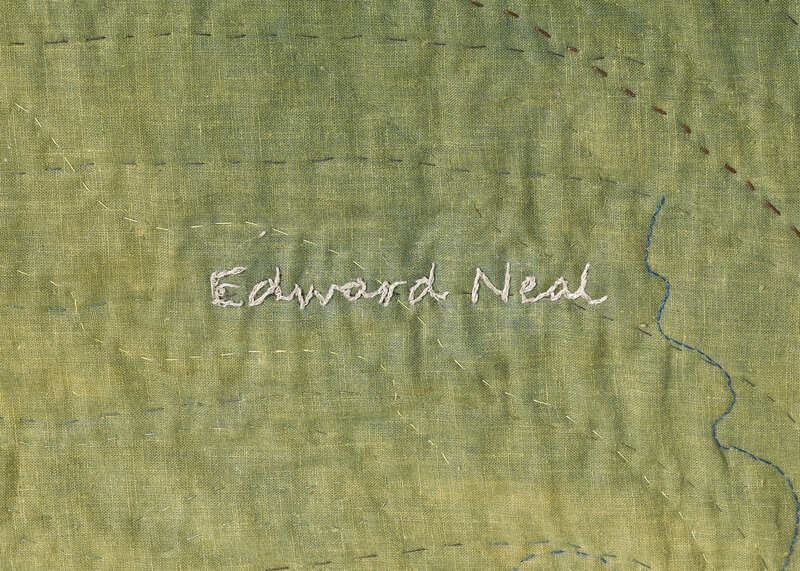

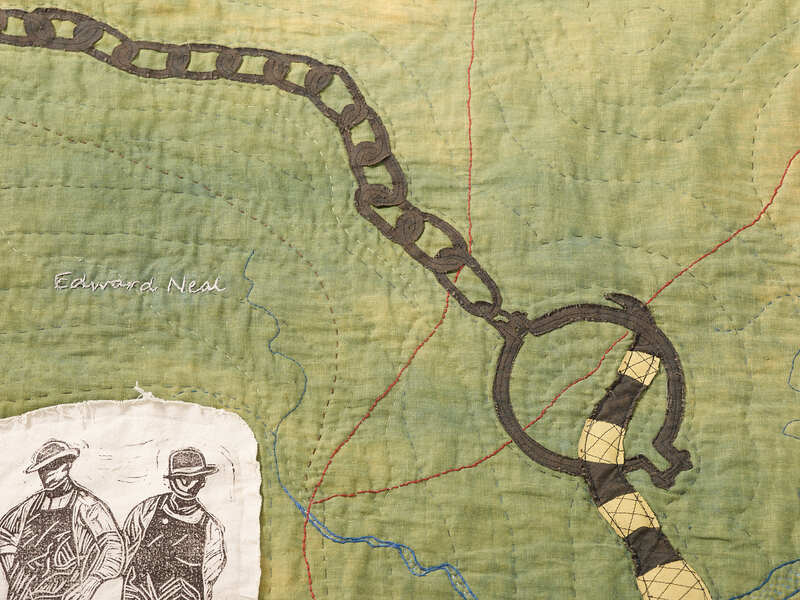

Edward Neal

Dan W. Stephens

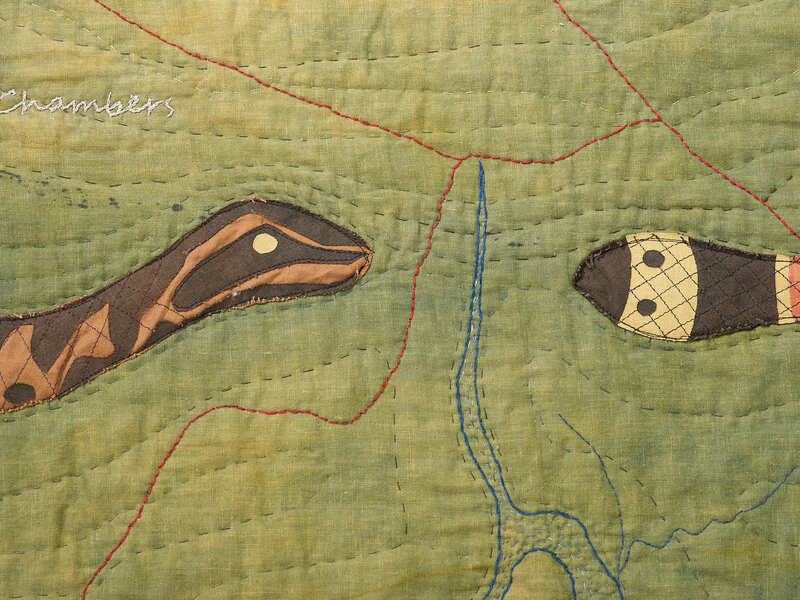

and Willie Frank Chambers.

We know that they were sentenced to time in a prison labor camp outside of Anguilla, GA after being convicted of crimes like robbery, burglary, larceny. We know that they were shot dead by the camp warden and guards on July 11th, 1947. But we know very little more than that. We don’t have pictures of them, there are no interviews with their families. We don’t know if they had children or people who mourned their deaths. The only reason we know what little we do know about them is because of the dedicated organizing by the NAACP to bring attention to their deaths.

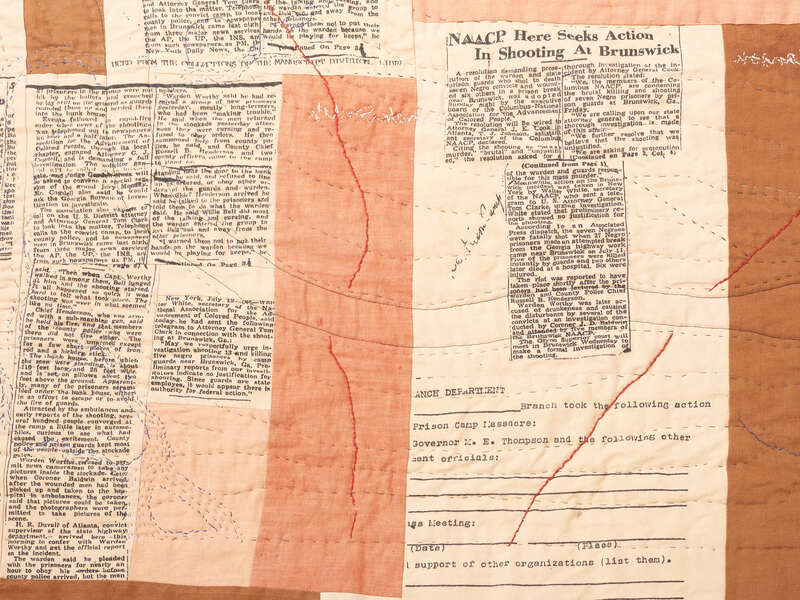

The day after their murder the New York Times ran a story describing their killing as a failed escape attempt. That was the official story. But a hand written letter from one of the survivors that made it to the local NAACP chapter, told a different story. Investigations by NAACP members revealed that the men had been forced to dig ditches without shoes in swampy land infested with poisonous snakes. When they refused to continue working, afraid for their safety, they were driven back to the camp where the warden, drunk and angry, open fire on them with a submachine gun. Thanks to their advocacy, there were public hearings and eventually a trial. Although no one was ever convicted of the killings, the fact that we know as much as we do today is because of their tireless efforts for justice.

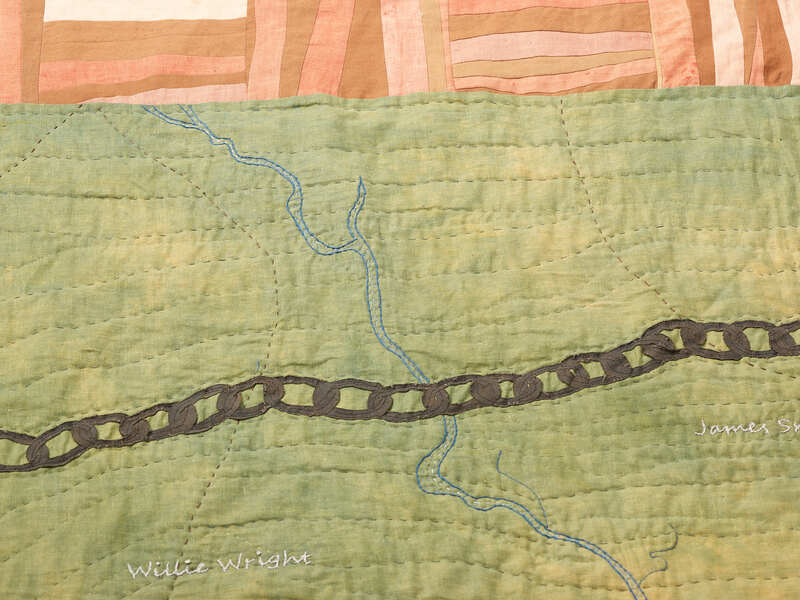

It felt daunting to begin telling this story when so much was unknown. It’s not even clear where the men were killed. Although the prison camp operated for at least four years, I could only find its location listed as being several miles outside of the town of Anguilla. The only place I could think of beginning was with the land. The land in Georgia had been transformed by the hands of Black people in bondage for 500 years, beginning with the introduction of enslaved Africans to the land in 1526. Although this system of racist exploitation officially ended with the end of the Civil War, in other ways it just changed its trappings. The Government of Georgia began leasing convicts to landowners to replace their captive workforce as early as 1868. “Black Codes” were passed across the South which criminalized every aspect of free Black life including vagrancy, unlawful assembly, interracial relationships, selling agricultural produce without written permission of an employer, or practicing any occupation other than farmer or servant under contract without written permission from a judge. [1] The prison population exploded during Reconstruction and the years following, and even as reformers limited the leasing of convicts to private businesses in the early 20th century, chain gangs were employed to build roads in almost every county of the state. When I asked a state archivist which highways in Georgia were built using prison labor, she answered “all of them.”

So I thought about the land and the men working it. They worked hemmed in by death, caught between system of violent subjugation on one side of them and literal poisonous snakes on the other. I also thought about materials, about cotton and fabric, and how its history also played into these systems of death. How cotton’s rise depended on the labor of enslaved Black people, the displacement of native communities, and the crushing labor conditions of textile factories in the north.

I decided to make the quilt out of a rough spun hemp and cotton blend, and to dye it with natural dyes – plants and trees that would all grow in the region where these men lived and died (I didn’t source my dye materials from the region – given the time frame and constraints of the pandemic, it seemed too challenging).

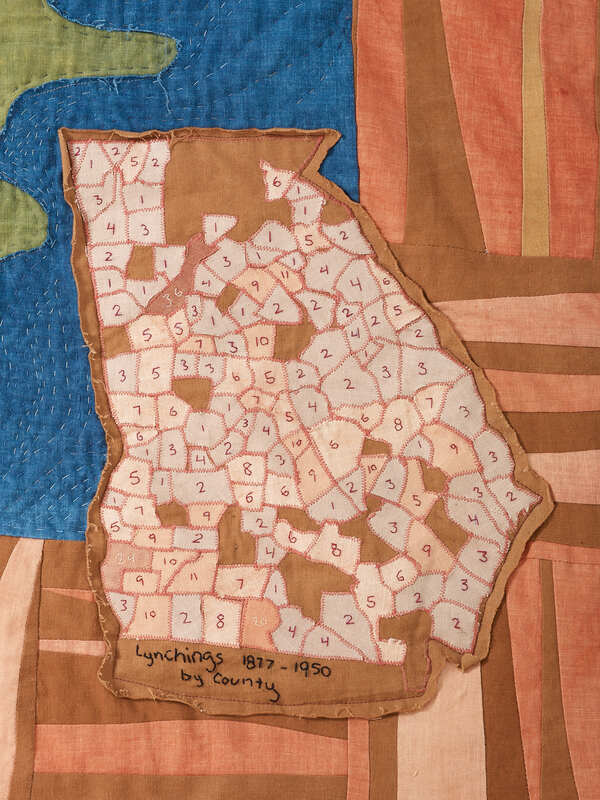

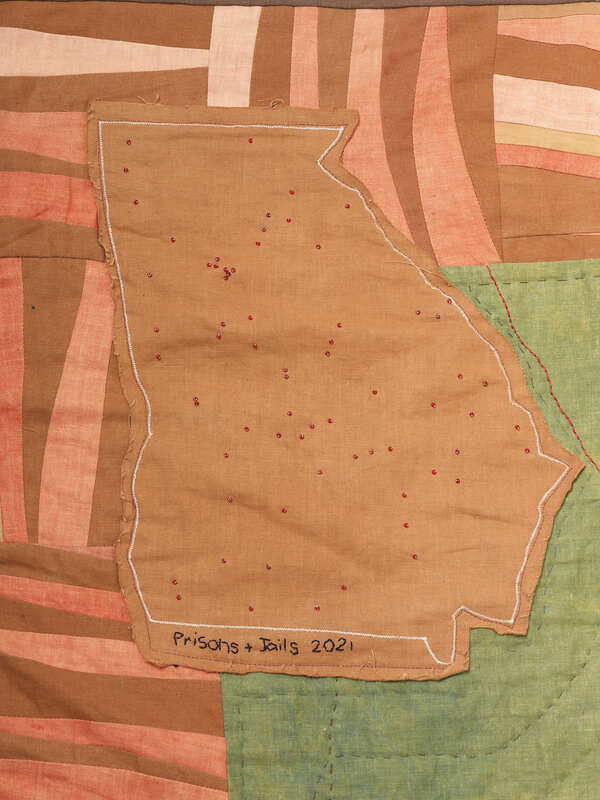

The only photo I had of the men or the prison camp was a newspaper photograph of their dead bodies, stretched out in the dirt in front of their barracks. As a white artist making work about the history of white supremacy and state violence against Black people, I try to be thoughtful about the ways I tell these stories. I have heard again and again from friends and collaborators about the trauma created by the constant flow of images of Black death and violence against Black people and communities. I knew that that wasn’t an image I would use in my piece, so instead I turned to maps. Maps of the land and the roads they were building, but also maps that told the stories behind the story of their death. A map of the enslaved population in Georgia on the eve of the civil war. A map of jails and prisons across Georgia today. A map of lynchings, by county, between 1877 and 1950 (on which the Anguilla prison massacre is not counted). A map of police killings between 2010 and 2020.

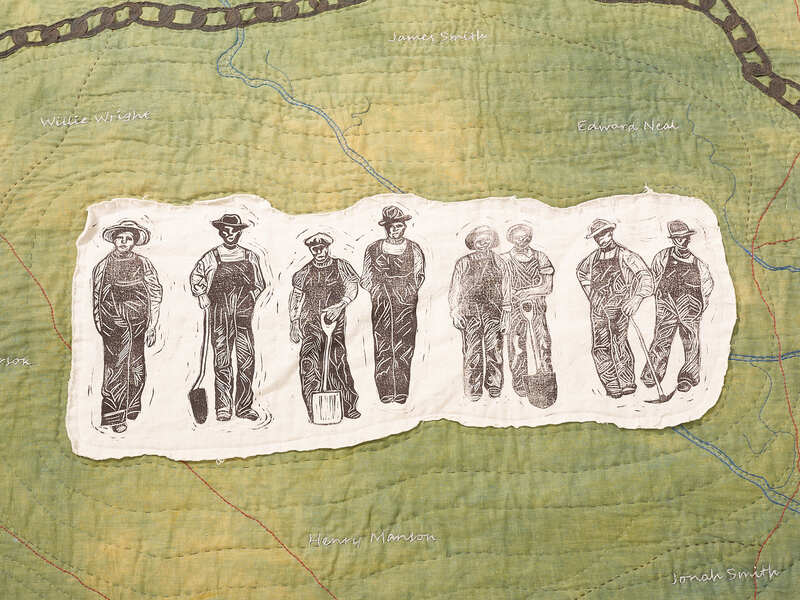

In the center of the quilt is a block print based on a photo of a chain gang in the early 1930s. Since I had no photos of the men themselves, this photo could stand in their place. I picked it for the dignity of the men visible in their faces and bodies, and the fact that they were not wearing striped prison uniforms which rob prisoners of their identities and individuality. Around them are the twin threats of incarceration and snakes.

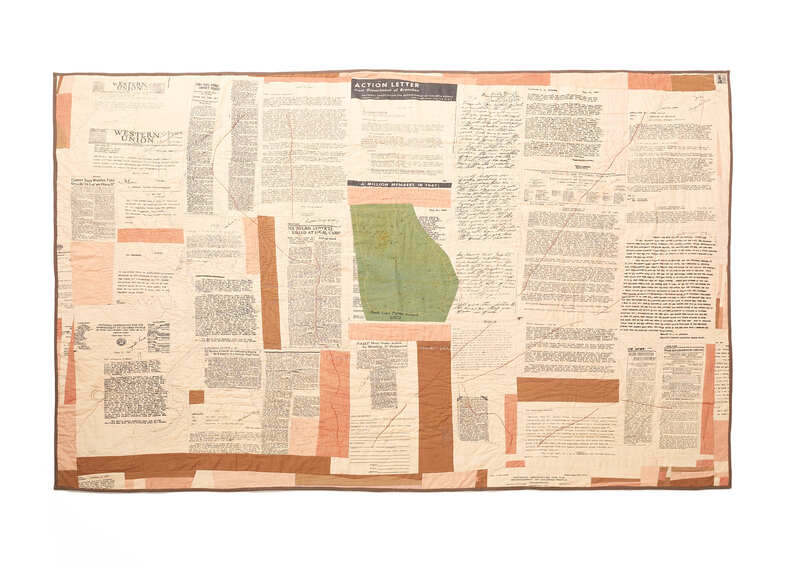

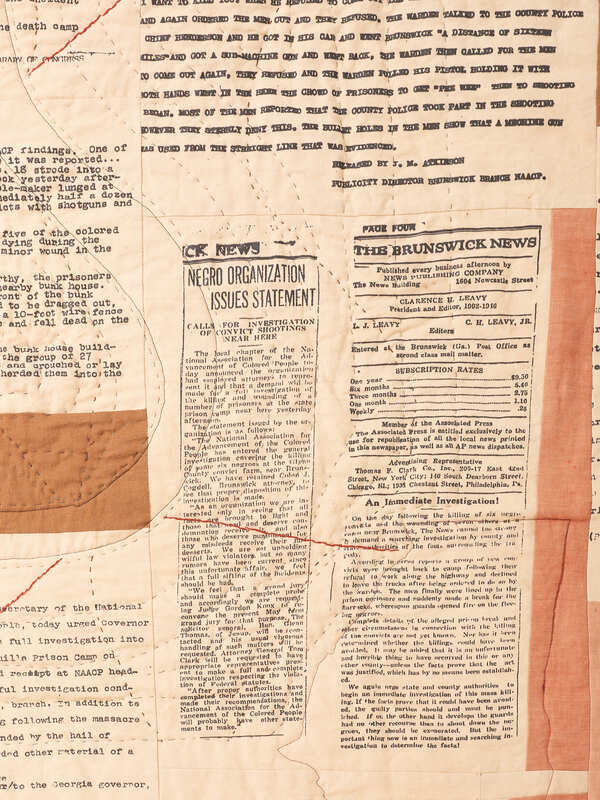

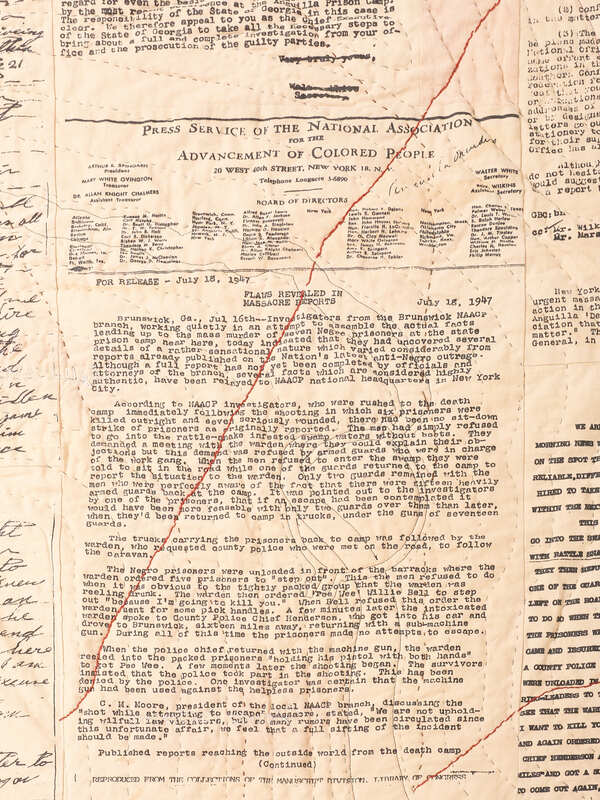

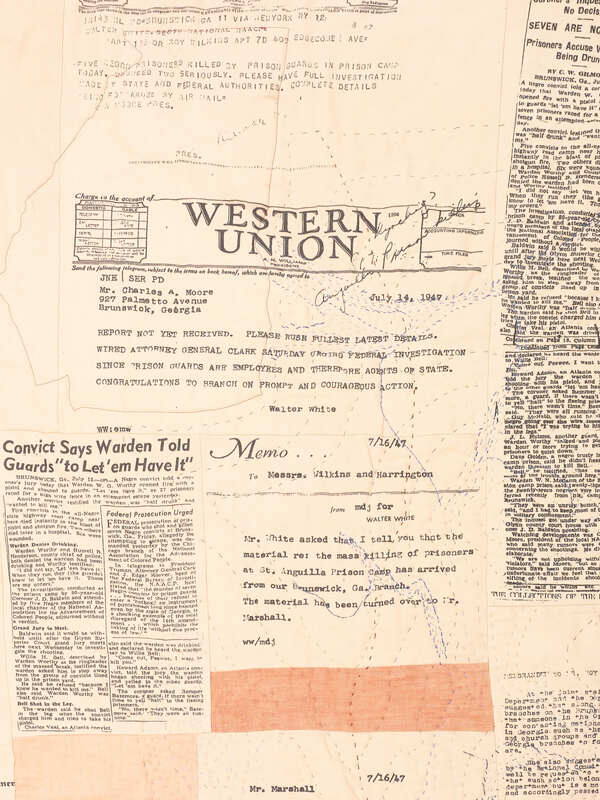

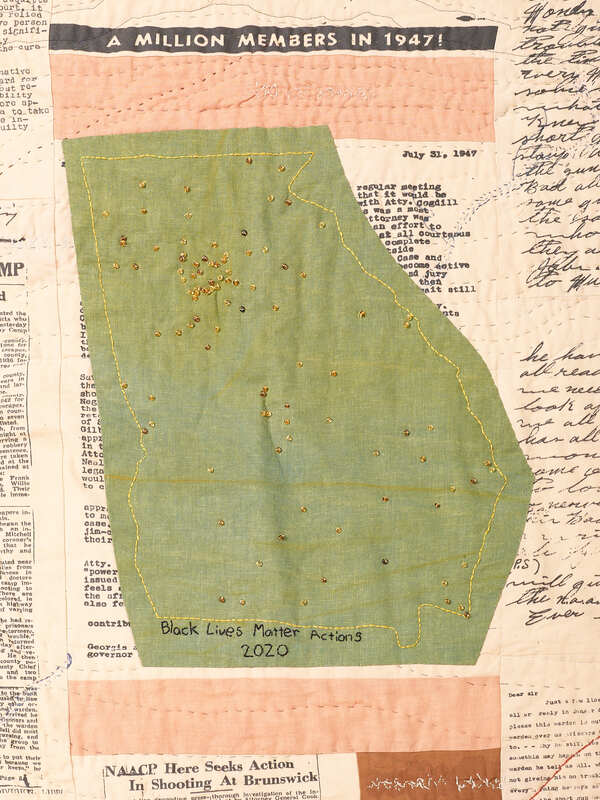

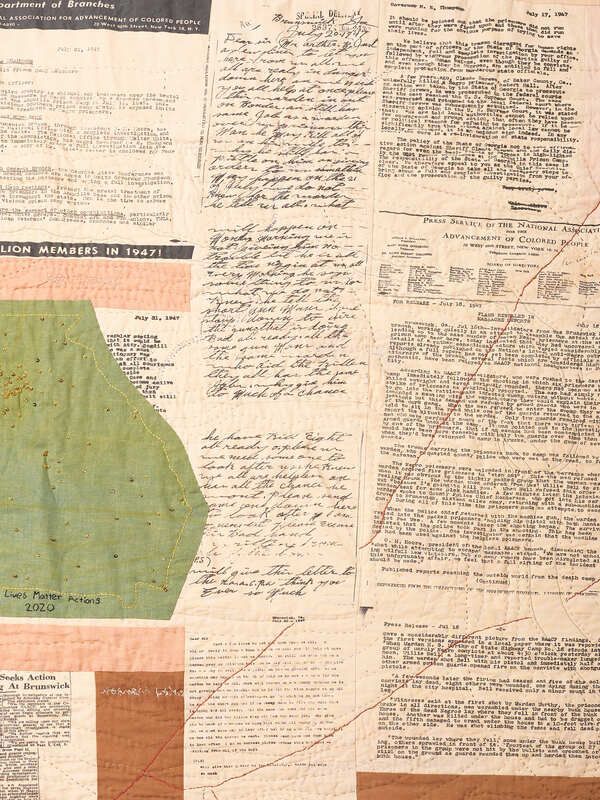

As I worked on the project over the course of my residency, I checked in with Mariame for advice and feedback as the quilt evolved. As the front of the quilt took shape, we were chatting about working from the primary source materials from the NAACP archive. Mariame mentioned a desire to include some of the documents from the archive. Not only were they a trove of historical information, but they also documented years of struggle in Georgia and across the country to demand justice in this case. And so the back of the quilt was born. If the front of the quilt is a roadmap of oppression, of violent subjugation of Black people in America, the back of the quilt is a map of resistance. Printed on fabric and sewn together are dozens of pieces of ephemera documenting the history of the case and the organizing that it ignited. In the center is one final map, a map of Black Lives Matter actions across Georgia in 2020. Although this country is built on a foundation of white supremacy and exploitation, it is also built on a history of resistance, rebellion, and movements for justice and abolition.

[1] https://www.crf-usa.org/brown-v-board-50th-anniversary/southern-black-codes.html

Rachel Wallis in collaboration with Mariame Kaba

Created during a 2020-2021 Project Nia Artist Residency

7.5 ft x 5 ft

Plant dyed and linoleum block printed and digitally printed cotton, hemp and linen fabric, embroidery and hand quilting thread, glass beads, block printing ink, cotton batting.

Photographed by Bryce Laughlin Photography

When Mariame Kaba invited me to be the first Project Nia artist in residence, and create a quilt illustrating the history of a group of prison laborers killed by their captors in Georgia in the 1940s, I was both honored and overwhelmed. Every quilt tells a story. They tell the story of births, marriages, and deaths. They tell stories with the materials they are made of; the techniques used; the love, and time, and labor invested in their creation. And they have been used by incredible artists and makers for centuries to tell powerful stories of resistance, love, family, and loss in communities around the world.

At the same time, the story of the Anguilla prison massacre is not an easy one to tell. We know so little about the victims and the circumstances surrounding their deaths. We have their names:

Jonah Smith

Henry Manson

Willie Wright

James Smith

George Patterson

Edward Neal

Dan W. Stephens

and Willie Frank Chambers.

We know that they were sentenced to time in a prison labor camp outside of Anguilla, GA after being convicted of crimes like robbery, burglary, larceny. We know that they were shot dead by the camp warden and guards on July 11th, 1947. But we know very little more than that. We don’t have pictures of them, there are no interviews with their families. We don’t know if they had children or people who mourned their deaths. The only reason we know what little we do know about them is because of the dedicated organizing by the NAACP to bring attention to their deaths.

The day after their murder the New York Times ran a story describing their killing as a failed escape attempt. That was the official story. But a hand written letter from one of the survivors that made it to the local NAACP chapter, told a different story. Investigations by NAACP members revealed that the men had been forced to dig ditches without shoes in swampy land infested with poisonous snakes. When they refused to continue working, afraid for their safety, they were driven back to the camp where the warden, drunk and angry, open fire on them with a submachine gun. Thanks to their advocacy, there were public hearings and eventually a trial. Although no one was ever convicted of the killings, the fact that we know as much as we do today is because of their tireless efforts for justice.

It felt daunting to begin telling this story when so much was unknown. It’s not even clear where the men were killed. Although the prison camp operated for at least four years, I could only find its location listed as being several miles outside of the town of Anguilla. The only place I could think of beginning was with the land. The land in Georgia had been transformed by the hands of Black people in bondage for 500 years, beginning with the introduction of enslaved Africans to the land in 1526. Although this system of racist exploitation officially ended with the end of the Civil War, in other ways it just changed its trappings. The Government of Georgia began leasing convicts to landowners to replace their captive workforce as early as 1868. “Black Codes” were passed across the South which criminalized every aspect of free Black life including vagrancy, unlawful assembly, interracial relationships, selling agricultural produce without written permission of an employer, or practicing any occupation other than farmer or servant under contract without written permission from a judge. [1] The prison population exploded during Reconstruction and the years following, and even as reformers limited the leasing of convicts to private businesses in the early 20th century, chain gangs were employed to build roads in almost every county of the state. When I asked a state archivist which highways in Georgia were built using prison labor, she answered “all of them.”

So I thought about the land and the men working it. They worked hemmed in by death, caught between system of violent subjugation on one side of them and literal poisonous snakes on the other. I also thought about materials, about cotton and fabric, and how its history also played into these systems of death. How cotton’s rise depended on the labor of enslaved Black people, the displacement of native communities, and the crushing labor conditions of textile factories in the north.

I decided to make the quilt out of a rough spun hemp and cotton blend, and to dye it with natural dyes – plants and trees that would all grow in the region where these men lived and died (I didn’t source my dye materials from the region – given the time frame and constraints of the pandemic, it seemed too challenging).

The only photo I had of the men or the prison camp was a newspaper photograph of their dead bodies, stretched out in the dirt in front of their barracks. As a white artist making work about the history of white supremacy and state violence against Black people, I try to be thoughtful about the ways I tell these stories. I have heard again and again from friends and collaborators about the trauma created by the constant flow of images of Black death and violence against Black people and communities. I knew that that wasn’t an image I would use in my piece, so instead I turned to maps. Maps of the land and the roads they were building, but also maps that told the stories behind the story of their death. A map of the enslaved population in Georgia on the eve of the civil war. A map of jails and prisons across Georgia today. A map of lynchings, by county, between 1877 and 1950 (on which the Anguilla prison massacre is not counted). A map of police killings between 2010 and 2020.

In the center of the quilt is a block print based on a photo of a chain gang in the early 1930s. Since I had no photos of the men themselves, this photo could stand in their place. I picked it for the dignity of the men visible in their faces and bodies, and the fact that they were not wearing striped prison uniforms which rob prisoners of their identities and individuality. Around them are the twin threats of incarceration and snakes.

As I worked on the project over the course of my residency, I checked in with Mariame for advice and feedback as the quilt evolved. As the front of the quilt took shape, we were chatting about working from the primary source materials from the NAACP archive. Mariame mentioned a desire to include some of the documents from the archive. Not only were they a trove of historical information, but they also documented years of struggle in Georgia and across the country to demand justice in this case. And so the back of the quilt was born. If the front of the quilt is a roadmap of oppression, of violent subjugation of Black people in America, the back of the quilt is a map of resistance. Printed on fabric and sewn together are dozens of pieces of ephemera documenting the history of the case and the organizing that it ignited. In the center is one final map, a map of Black Lives Matter actions across Georgia in 2020. Although this country is built on a foundation of white supremacy and exploitation, it is also built on a history of resistance, rebellion, and movements for justice and abolition.

[1] https://www.crf-usa.org/brown-v-board-50th-anniversary/southern-black-codes.html